Unmasking Abuse: Anonymity and Accountability on Social Media

By giving us an open platform to share our thoughts in real-time, social media has become central to self-expression in today’s world, providing almost everyone with an opportunity to be heard. But the democratic design of social networking sites that have been central to their success — accessibility and immediacy — is a double-edged sword. For every post of positivity or social uplift found on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, there are scores of abusive messages which anonymous users are able to post with impunity.

Hate speech, cyberbullying, trolling. Dressed up in different ways, online abuse has been an ever-present part of social media since its inception. Discussion boards have long been playgrounds for alt-right exponents and anti-feminist incels. Vulnerable teenagers have been coaxed to self-harm and suicide by strangers. Any minority person in the public eye faces death threats and bigoted drivel in their DMs.

Anonymity is the enabling force behind many of these displays of hate. Absolved of any personal risk, cowardly individuals are emboldened to attack others in a way that they would never even conceive of in the offline world — as they’d surely get their head kicked in. Targets of abuse are seen less as a human being with complex emotions and vulnerabilities than as another faceless profile amongst thousands to jeer at.

In this way, social media lends itself to abuse. And regulators have so far been unable, or perhaps unwilling, to get to grips with the issue. Every week there is a new victim — a footballer, activist or influencer — stepping forward to expose hate in their direct messages. A wave of failed prevention strategies begs the question: can online abuse really be stopped without compromising the design that has made social media so popular?

Let’s begin with some of the prevention measures taken at the level of the general public. The football world, a flashpoint for social media harassment in the UK, has been key in bringing the topic of online abuse into mainstream discourse. Dozens of high-profile players such as Raheem Sterling, Marcus Rashford and Son Heung-min have used their large followings to discuss their experiences of being racially abused online.

| Rashford’s tweet captures the all-too-normalised nature of racist abuse online |

Seeking to strike at the core of the issue and change attitudes, several awareness campaigns have been mobilised by the football community. The #SayNoToRacism message has been widely endorsed on social media for many years now, but non-white players still face racist abuse every time they log in to their accounts.

Earlier this year, restless with continued online abuse, players, clubs and sporting bodies participated in a four-day boycott of all social media as part of the #StopOnlineAbuse campaign. When they returned to social media in the weeks following the online blackout, footballers were met with the same hate in their private messages. A joint report by sports integrity firm Quest and data science company Signify found that 14 Premier League players were subjected to racist abuse on the final day of the season alone.

Clearly, there is still a long way to go. In spite of the increasing visibility of anti-racist sentiment, with player testimonies and online activism, discrimination endures. The case of football underlines that there will always be people inclined to abuse; what will make a difference is divesting them of the tools to do so.

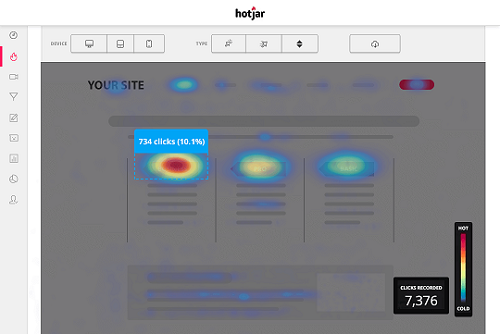

Social media companies have their own systems in place to monitor abusive content, but these have faced criticism from the outside and from within. When a removal request is made on a site like Facebook or Twitter, the feedback time can vary depending on the number of staff working at that moment, as well as the number of other requests ahead in the queue. At its slowest, this may mean an abusive message stays up for days at a time.

And what of the poor souls tasked with trawling through these requests? The New Yorker reported on this invisible world in 2019. More than a hundred thousand people work as online content moderators, filtering through and deleting the most extreme posts, struggling through an unending backlog of abuse. Many of these workers consider themselves underpaid and undervalued by their employers. Many also suffer mentally as a result of everyday exposure to foul messages. Support systems exist, but are often insufficient.

Content moderating teams are generally supported by the automated response, which has its own flaws. Most sites deploy algorithms to detect and automatically delete hate speech, but this leaves room for certain messages, such as those using emojis, to slip through the net.

Social media companies could and probably should be investing more in user safety. Two-thirds of UK adults want greater regulation of social media, according to Ofcom’s annual Online Nation report for 2020. Specifically, critics call for more sophisticated automated systems, higher numbers of dedicated content monitoring staff, and greater transparency from these companies on the work they do to stamp out abuse through regular reports.

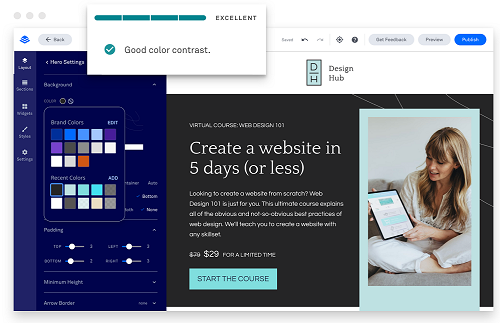

One more radical proposal is to introduce identity verification as part of membership to social networks, thereby removing the veil of anonymity that has so far protected online abusers. Manchester United captain Harry Maguire supported this idea back in 2019 following racist abuse of his teammate Paul Pogba. This proposal gathered further momentum in the UK this year following a petition tabled by celebrity Katie Price, who was moved following online abuse directed at her son Harvey, who has a learning disability. The petition received over 180,000 signatures and was subsequently debated in parliament in May.

| In light of continued abuse, more profound changes to social media have been sought |

The UK government responded by raising doubts about the knock-on effects of this new measure. “User ID verification for social media could disproportionately impact vulnerable users and interfere with freedom of expression”. The main contention is that anonymity is vital for protecting individuals exploring their gender or sexual identity, as well as whistleblowers and journalists’ sources. This is pretty hard to argue with. Do we also want to freely submit our personal information to social media companies with a history of selling their users’ data for profit? I don’t think so.

In any case, these companies are unlikely to ever agree to these revised terms of membership. It is in their interest to enlist new users, not deter them with added hoops to jump through upon registration. And even if identity verification was enforced, there is no guarantee that it would eradicate online abuse overnight; many trolls are brazen enough to offend with their faces and full names emblazoned on their profile. The motive is in the right place, but in practice identity verification falls down pretty quickly.

With small pockets of users still intent on spreading hate, and social media companies sluggish to respond, this only leaves one key player to take up the mantle: governments. This past year, particularly, has seen a move towards more governmental intervention in monitoring online abuse, as they try to succeed where others have failed.

In February, Australia introduced its Online Safety Bill, which aims to hold social media companies to account by giving the Australian government legal powers to fine them for failing to remove harmful content. The UK has since drafted its own Online Safety Bill, which ascribes similar regulatory authority to Ofcom. The premise of these new laws is that social media companies now have a financial incentive (through fines) to be more proactive in removing abusive content hosted on their sites.

| The new bill has been hailed as a watershed moment, but the jury is still out |

This all sounds good in theory, but the bills have not come without objection. The main sticking point has been in demystifying the grey area of content that is deemed "lawful but harmful", which will now be liable for removal from social media sites. Defining harm is a subjective and therefore polarising endeavour. With this now falling under the remit of governments ministers and Ofcom administrators, each with their own views on what constitutes harm, are we any closer to finding an airtight procedure for dealing with online abuse? Is this even possible?

Content monitoring is a thankless task. As the onus shifts towards government bodies as the main arbiters of online safety, we can only be certain that it’s a problem that’s not going away. Personally, I’m not sure we will ever find a middle ground between anonymity and accountability. In the online world, these seem like two mutual exclusives always pulling in opposite directions.

Tom Morris / Editor & Writer at Social Songbird

Recent English graduate with experience in travel and current affairs writing. An aspiring digital marketer with a big appetite for postmodern fiction, crime documentaries and Hispanic culture.

Unmasking Abuse: Anonymity and Accountability on Social Media

Reviewed by Tom Morris

on

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by Tom Morris

on

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by Tom Morris

on

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by Tom Morris

on

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Rating:

Entrepreneur, international speaker on Social Media Marketing. First one in the UK to write and speak in conferences about Twitter as a marketing tool. Consultant to Corporate Companies, Government Organizations, Marketing Managers and Business Owners.

Entrepreneur, international speaker on Social Media Marketing. First one in the UK to write and speak in conferences about Twitter as a marketing tool. Consultant to Corporate Companies, Government Organizations, Marketing Managers and Business Owners. Aspiring novelist with a passion for fantasy and crime thrillers. He hopes to one day drop that 'aspiring' prefix. He started as a writer and soon after he was made Executive Editor and Manager of the team at Social Songbird. A position he held for 5 years.

Aspiring novelist with a passion for fantasy and crime thrillers. He hopes to one day drop that 'aspiring' prefix. He started as a writer and soon after he was made Executive Editor and Manager of the team at Social Songbird. A position he held for 5 years. Musician, audio technician, professional tutor and a Cambridge university English student. Interested in writing, politics and obsessed with reading.

Musician, audio technician, professional tutor and a Cambridge university English student. Interested in writing, politics and obsessed with reading. Recently graduated with a BA in English Literature from the University of Exeter, and he is about to study an MA in Journalism at the University of Sheffield. He is an aspiring journalist and novelist; in his free time he enjoys playing chess, listening to music and taking long walks through nature.

Recently graduated with a BA in English Literature from the University of Exeter, and he is about to study an MA in Journalism at the University of Sheffield. He is an aspiring journalist and novelist; in his free time he enjoys playing chess, listening to music and taking long walks through nature. Lucy is an undergraduate BSc Politics and International Relations student at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Lucy is an undergraduate BSc Politics and International Relations student at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Anna Coopey is a 4th year UG student in Classics at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. She is a keen writer and researcher on a number of topics, varying from Modern Greek literature to revolutionary theory.

Anna Coopey is a 4th year UG student in Classics at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. She is a keen writer and researcher on a number of topics, varying from Modern Greek literature to revolutionary theory.